Shapeshifting protein

Most proteins have a distinctive shape that influences which other molecules they interact with. WSU molecular biologist Ray Reeves works with a remarkable protein that has no shape of its own.

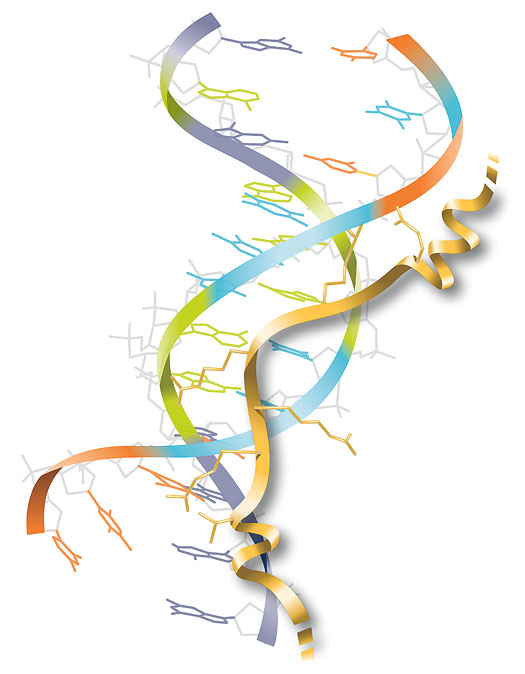

Reeves found that the protein, HMGA, slips into the narrow groove of the double helix in regions of DNA that are rich in A (adenine) and T (thymine). As HMGA binds to the DNA with its "AT hooks," it changes the shape of the DNA enough to allow other proteins to turn genes on or off. HMGA promotes cell division and, in adults, is a biomarker for cancer. WSU biochemist Alex Li is developing a test for the presence of HMGA based on the protein's ability to change the shape of AT-rich DNA.

WSM STAFF ILLUSTRATION

In stretches of DNA that are composed of adenine (A) and thymine (T), with no cytosine (C) or guanine (G), the two strands of the double helix are especially close together. HMGA recognizes the narrow groove between them.

In this diagram, HMGA (gold) has inserted part of itself,

called an AT hook, into the groove of a brief stretch of

AT-rich DNA. Branches (![]() ) of the HMGA secure its

attachment to the DNA. Two more AT hooks at either end

of the HMGA may bind to other AT-rich areas nearby (not

shown). If two or three of its AT hooks find places to

bind, HMGA alters the structure of the DNA enough to

allow other proteins to turn genes on or off.

) of the HMGA secure its

attachment to the DNA. Two more AT hooks at either end

of the HMGA may bind to other AT-rich areas nearby (not

shown). If two or three of its AT hooks find places to

bind, HMGA alters the structure of the DNA enough to

allow other proteins to turn genes on or off.

Photo of Ray Reeves by Robert Hubner.

Raymond Reeves, Ph.D. :: Center for Reproductive Biology, School of Molecular Biosciences :: Areas of focus include the study of protein-DNA interactions involved with the regulation of gene transcription and DNA repair of genes in normal and cancerous human cells; chromatin structure and function; the mammary gland.