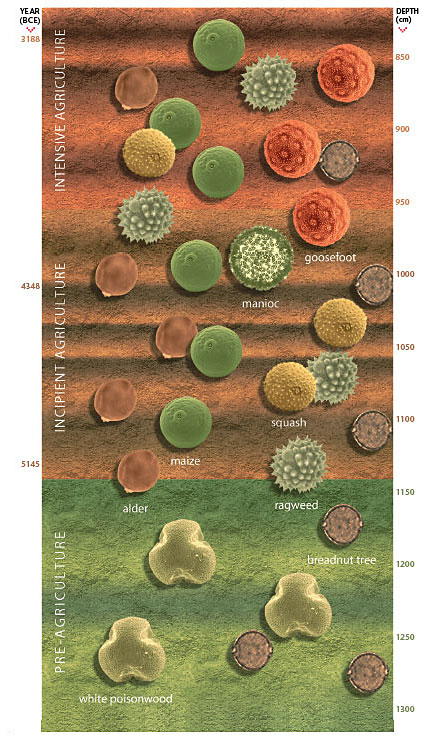

Pollen reveals climate change through the history of agriculture

Jones traces changes in climate, and how human societies responded to those changes, by examining pollen grains trapped in lake and estuary sediments. Pollen is tiny but incredibly durable; as long as it stays completely dry or completely wet, he says, it lasts just about forever. He has easily identified pollen grains more than 300 million years old.

On field expeditions, Jones and his graduate students use a five-horsepower motor to drive a coring tube deep into sediment near village sites being investigated by other archaeologists. The team they work with includes experts on soils, cultural artifacts, radiocarbon dating, and tiny plant crystals called phytoliths, but Jones goes first, using pollen to sketch the major event horizons in the core. "We'll say, 'Hey look, something's happening at 180 centimeters below the surface, and another one at 400 centimeters. Let's get radiocarbon dates on these right now, because that takes a little time.'" After he lays out the basic framework, he and the others go back and fill in the details.

His three-inch-wide, 11- to 15-yard-deep cores record a vast span of environmental and human history. They go deep enough to reach material laid down before people settled the area. Jones and his colleagues recently showed that agriculture in the New World began around 5200 BC, significantly earlier than previously thought. It was driven in part by population growth and the need for a reliable food supply, and in part by a change in climate that made cultivation more likely to succeed.

In Washington State University anthropologist John G. Jones's soil cores, pollen tells the tale: When early Mesoamericans began cultivating crops, trees such as poisonwood were replaced by edible plants such as maize, squash, manioc, and breadnut trees. Sun-loving alders became more abundant as forests were cleared, and pest plants like ragweed and goosefoot thrived alongside the crops. Large-scale burning to clear land left bands of charcoal throughout the agricultural period. Shallower portions of the cores (not shown) bear evidence of drought, erosion, crop failure, and social collapse.

ILLUSTRATION BY AARON ASHLEY

Photo of John G. Jones by Robert Hubner.

John G. Jones, Ph.D. :: Department of Anthropology, College of Liberal Arts :: Areas of focus include origins of agriculture particularly in Mesoamerica, pollen, landscape and vegetation reconstruction, palynology applied to law enforcement.