Personal tools

Help

Tools

Class Notes

- Do you have news for fellow WSU alumni and other readers of Washington State Magazine? Send us your class note.

Our Story

written by alumni, faculty and friends.

NOTE: THIS IS A LEGACY SITE AND IS NOT REGULARLY MAINTAINED

Views

A Sense of Place: Gardening on the Palouse

From Our Story

By Tonie Fitzgerald

From Washington State Magazine, Summer 2004

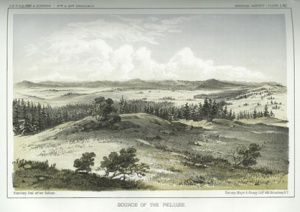

Some gardeners in the area are joining forces with other plains dwellers of our nation in creating what have come to be called prairie gardens. Prairie gardens comprise the grasses and wildflowers that flourish in open, sunny spaces. Think of meadows with tall grasses waving back and forth in gentle breezes. Think of plants with nodding, bonnet-shaped flowers gracing the landscape with drifts of blues, purples, pinks, yellows, and reds. (Think television commercials for allergy medicines!) Prairie gardens recall the land as it looked prior to the advent of our modern landscapes of large-scale agriculture, suburbia, and urban sprawl. They also provide refuge for the diminishing number of plants that once dominated our grassland communities.

Actually, there are three types of plant communities in the Palouse: grassland, butte, and riparian. Gardeners may choose from among the plants that naturally occur in these communities to plan a garden area with more structural diversity than is found in a typical prairie garden.

A grassland plant community is dominated by perennial bunchgrasses interspersed with wildflowers that thrive in open sunny areas, such as lawns. Gardeners can replace their lawns, or portions of them, with native perennial bunchgrasses and flowers to create a prairie garden.

Idaho fescue, bluebunch wheatgrass, blue eyed grass, biscuit root, arrowleaf balsamroot, shooting stars, brodeas, kittentails, and prairie smoke are all native to the Palouse.

The butte plant communities occupy the peaks and ridges that rise above the Palouse, such as Steptoe and Kamiak buttes. The south-facing slopes are sunnier than the north sides and dry out sooner in the spring. They support shrubs such as hawthorne, serviceberry, mock orange, and wild roses, as well as lupine, arrowleaf balsam root, and paintbrush. The ridgetops are the driest sites on the Palouse and are populated by Ponderosa pines, snowberry shrubs, glacier lilies, spring beauties, yellow bells, and Clarkia flowers. The north slopes remain cooler and wetter longer into the spring. Here you see Douglas fir, larch, and pine trees as well as the shade-loving trillium flowers, fairy bells, Solomon’s seal, and calypso orchids.

The third type of plant community in the Palouse is the riparian community, which runs along the creeks and drainages. These water sources support thickets of trees, hawthorne shrubs, and wild roses where deer, coyote, and birds find shelter and food.

Creating a Palouse Prairie Garden

If you want to reclaim a bit of the original Palouse prairie on your own property, replete with songbirds and butterflies, you can access a growing body of information on creating prairie gardens. A true grassland prairie garden of grasses and wildflowers needs to be in an open area in full sun. Start with clean, weed-free soil and seed it with a custom mix of native grasses and/or wildflowers available at any of the local seed companies listed here.

Do not use generic “wildflower” mixes. They contain quick-growing species that become invasive, such as California poppies, or even weeds. Your prairie garden will soon be taken over by these nonnative types.

If areas on your property mimic the microclimates found on hillsides, such as north sides of buildings or south facing walls, don’t be afraid to try some of the native trees and shrubs from the Butte plant community. The varied heights, forms, and textures will add interest for you and the birds who miss the plants of a bygone era.

A WSU/Spokane County extension agent in horticulture, Tonie Fitzgerald is author of Gsrdening in the Inland Northwest (Washington State University 2001).

Palouse-Area Seed Companies

Grassland West

Clarkston Washington 99403

509-758-9100

http://www.grasslandwest.com

Rainier Seeds

Davenport, Washington 99122

509-725-1235

Plants of the Wild

Tekoa, Washington 99033

509-284-2848

Also, see WSU’s Ownbey Herbarium Web site.

Our Story site map

Our Story main page | Our Story categories | Help Desk

Contact | Give | Advertise

Washington State Magazine | Washington State University | Class Notes

Our Story is coordinated by

In partnership with

Our Story and Washington State Magazine are publications of Washington State University. All rights reserved.

P.O. Box 641227, Washington State University, Pullman, WA 99164-1227 USA | wsm@wsu.edu, 509-335-2388

Accessibility | Copyright | Policies