Personal tools

Help

Tools

Class Notes

- Do you have news for fellow WSU alumni and other readers of Washington State Magazine? Send us your class note.

Our Story

written by alumni, faculty and friends.

NOTE: THIS IS A LEGACY SITE AND IS NOT REGULARLY MAINTAINED

Views

Spokane's Foot and Mouth Disease outbreak in 1914

From Our Story

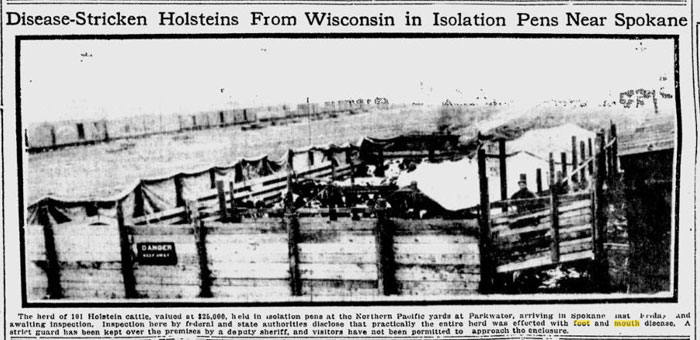

Courtesy WSU College of Veterinary Medicine

This issue is devoted to the value veterinarians bring to Washington’s economy and lifestyle. At the same time we are watching a sweeping Foot and Mouth Disease outbreak in South Korea. All veterinarians understand the profound negative impacts an outbreak of FMD would have in the state. But do you know about our last FMD cases and how Washington veterinarians stopped an epidemic?

On Tuesday, Nov. 10, 1914, the Washington State Department of Agriculture received a telegram stating two rail cars of cattle had left Wisconsin, bound for Roy, Washington. The 102 dairy animals had been unloaded, fed, and watered on the previous Friday at the Minnesota rail transfer station Near St. Paul.

By chance, the cattle had been penned in lots where previously, on Nov. 2, 125 other shipped cattle had received respite before moving to the Billings, Montana, stockyards and breaking out with FMD on Nov. 8. The same day, an outbreak on a train near Glendive, Mont., saw a railcar load of cattle stopped and the animals slaughtered by Major Dan Donohue, commander of the Montana Militia and head of the state’s Livestock and Sanitary Board. Donohue had committed a federal felony by stopping the train but the matter was never discussed. The telegram was a warning for Washington veterinarians and livestock officials to watch for the Roy-bound Northern Pacific train, which then was incommunicado somewhere in Montana and due to stop in Spokane.

The telegram was an unwelcome but not unexpected alert for Drs. F. H. Mason and C. M. McFarland, both with the federal Bureau of Animal Industry, and based in Washington state. Newspaper articles from Nov. 6, had declared that the U.S. was in the grips of the worst FMD epidemic in its history and its first outbreak since 1908.

The country still was decades away from its first antibiotics and the same week the cable was delivered, the discovery of the bacterium that causes gangrene was announced, crediting Drs. James Scarlett and Georges Des Jardins of the American Ambulance Service.

The famous Chicago Union Stockyards were closed for the first time since opening in 1865, idling some 35,000 workers and cutting off some $1.2 million in daily revenue. Movement of more than 100,000 cattle, sheep, and hogs was stopped. New York, Maryland, Indiana, Michigan, Illinois, and Pennsylvania were under a strict, statewide quarantine and Ohio was on the verge. Unbelievably however, cattle were being shipped for slaughter only to those states, excluding Chicago, and cut meat was under no embargo. Before the epidemic was stopped, every cattle market in the U.S. was affected, complete quarantines would be issued in 22 states, and more than 172,720 animals would be euthanized.

Large meetings of cattlemen, stockers, slaughter plant owners, and government officials were convened across the affected states. Speculation was that the FMD virus entered the U.S. in hog cholera serum imported from Europe and used by one farmer in Indiana. Threats were made on his life for bringing in the, “…dreaded scourge known as European Foot and Mouth Disease,” which had been implicated in the two most recent U.S. outbreaks.

In the end, most sources believe the epidemic’s spread was due in large part to the congregation of cattle brought earlier to Chicago for the National Dairy Show. Coincidentally, the winning cow that year establishing a new world record was “Lily of Willomoor,” owned by J. W. Clise of Seattle. Lily produced nearly 85,000 pounds of milk and more than 3362 pounds of butterfat in the previous year. In all, 30 of the 800 prized bulls and cows at the show were slated for destruction. The government relented, however, when the indemnity value of the animals approached a million dollars and owners devised a plan for self-quarantine. Lily escaped euthanasia.

In response to the allegations and threats made against the Hoosier producer, Indiana assistant state veterinarian, Dr. F. A. Bolser, made an emergency trip to Washington, D. C. to confer with President Woodrow Wilson’s Secretary of Agriculture, David F. Houston. At Houston’s request of Wilson, Congress was called into special session to passing an emergency appropriation intended to stave off further spread of FMD. World War I had begun in Europe, and now with the inevitable livestock depopulations already begun, the appropriation was passed handily in fear of a projected nationwide food shortage.

The Nov. 10, telegram ordered Drs. Mason and McFarland to quarantine all animals immediately when they arrived in Washington and await “subsequent developments.” The same day, Spokane’s Spokesman-Review newspaper in carried a front page story about the nation’s efforts to deal with the current FMD outbreak. It said all Bureau of Animal Industry agents were being ordered to trace back all shipments of cattle from any affected area over the last two months.

Aptly, the cattle arrived at Parkwater rail yard west of Spokane on Nov. 13—Friday the 13th—and were quarantined in pens specially constructed by the railway. Surprisingly, the cattle had made uninterrupted passage through the Idaho Panhandle despite that state’s voluntary quarantine that started Nov. 6. A photo from the day shows a wooden enclosure built with rough-cut lumber and railroad ties, swathed in carbolic acid-soaked canvas. At the rear is the entire train stopped on a siding.

The first cow examined had slight stomatitis. No other cows in the lot had any lesions or symptoms on this initial examination. When that single inflamed mouth was observed, the rail cars were quarantined, as were the railroad personnel and animal caretakers.

Washington had suffered five previous outbreaks of FMD in 1870, 1880, 1884, 1902, and 1904; the latter two far eclipsing the earlier events, perhaps due to increased rail transport of cattle.

Early on Nov. 16, a positive diagnosis of FMD was made jointly by state and federal veterinary inspectors, and by that time 51 animals in the shipment now had FMD lesions. Notice of what was to come was given to the animals’ owner, H. S. Royce and appraisal began. In the final analysis, Royce’s cooperation would be heralded as one of the keys to preventing a Washington outbreak.

Thirty-two purebred Holsteins were valued at $50 each, and the 70 grade Holsteins were worth $35 a head; estimated in values of beef, not dairy. Total value was $4,050, quite a sum at that time. In 1914, the average annual cost of living was about $50. In today’s dollars, accounting for inflation only, those 1914 dollars paid to Royce would be equivalent to more than $87,000.

In all from Oct. 1914, to March 1916, the U.S. government would spend more than $5 million in indemnities and expenses, matched by the affected states, once again to eradicate FMD.

Immediately after the check was delivered to David Munroe, (Royce’s agent), the killing and burning began. By Saturday, Nov. 21, all Roy-bound cattle had been euthanized and cremated along with the pens and litter. They were the last cattle killed in Washington for FMD.

Assisting in the depopulation and sanitation efforts were Washington State University veterinary students and faculty who took a train from Pullman to Spokane, after permission was granted by the veterinary dean, Dr. Sofus B. Nelson.

The rail cars became a concern because due to the war, carbolic acid, the preferred disinfectant, was in short supply as were materials to replace the cars. An agreement was reached, however, to use sodium hydroxide or formaldehyde as substitute disinfectants. The entire train in Spokane eventually was sanitized and made fit to carry more cattle. In Tacoma, 300 cattle cars were disinfected.

It is hoped, that the FMD cattle killed in 1914 will remain Washington’s last cows with that disease.

Our Story site map

Our Story main page | Our Story categories | Help Desk

Contact | Give | Advertise

Washington State Magazine | Washington State University | Class Notes

Our Story is coordinated by

In partnership with

Our Story and Washington State Magazine are publications of Washington State University. All rights reserved.

P.O. Box 641227, Washington State University, Pullman, WA 99164-1227 USA | wsm@wsu.edu, 509-335-2388

Accessibility | Copyright | Policies