Personal tools

Help

Tools

Class Notes

- Do you have news for fellow WSU alumni and other readers of Washington State Magazine? Send us your class note.

Our Story

written by alumni, faculty and friends.

NOTE: THIS IS A LEGACY SITE AND IS NOT REGULARLY MAINTAINED

Views

Pharmacy grew drug plants, considered selling them

From Our Story

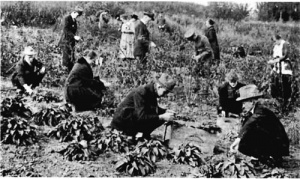

A project that Asa F. Maxwell began working on shortly after his arrival as head of the pharmacy program was the development of a medicinal plant garden. The place of pharmacognosy in the education of pharmacy students was very strong at that time, and it was common for colleges of pharmacy to maintain gardens so students might become familiar with plant identities, collection, drying and storage.

There also was a sharply increasing interest in the commercial growth of medicinal plants. A diminished supply of important drugs from Europe was a result of the shipping blockade in the Atlantic Ocean established by Germany during World War I (1914-18).

Commercial possibilities

Maxwell's uninhibited enthusiasm for the commercial growth of medicinal plants may be noted from a series of three articles published under his byline in the Spokane Chronicle newspaper. The purpose of the articles was to stimulate interest in the cultivation of medicinal plants in eastern Washington.

"Although eastern Washington is an ideal growing location for many valuable medicinal plants, this industry virtually is untouched," Maxwell stated. He made particular mention of belladonna, digitalis, hyoscamus, stramonium and althea as examples of plants that could be grown successfully.

The second article in the series provided information - including characteristics, uses and cultivation - about belladonna and digitalis. The third dealt with hyoscamus, stramonium and althea.

In the opening article, Maxwell claimed: "It is safe to say that hundreds of thousands of dollars annually is being paid out of this state for drugs that easily could be produced within 10 miles of the city of Spokane. An industry worth millions of dollars to the city could be built up with but little outlay of capital or expenditure of a great amount of land." He estimated that a belladonna crop would bring in $400 per acre.

He did include in the article the following admonition: "Unqualified statements concerning the ease and profitableness of drug plant growing must be taken with the proverbial 'grain of salt.'" Apparently, he viewed the statements he had made as realistic.

Nevertheless, the growth of the industry he promoted was never realized.

Collaborating to succeed

But as a result of Maxwell's efforts, a "Materia Medica Garden" came into existence in the spring of 1914. On March 7, Maxwell, with the cooperation of Oscar M. Morris, professor and head of the Department of Horticulture, requested that the Board of Regents "set aside a suitable tract of land, preferably one acre in area, and that arrangements be made whereby the cultivation and proper care of such tract will be provided for."

To justify the request, it was noted that "investigation and instruction in the cultivation of medicinal plants must be one of the prominent features in the curricula of schools of pharmacy," and that "a shortage already exists in the supply of many plants that can be successfully grown in this section of the United States."

It was suggested that the latter situation warranted the investigation of commercial possibilities as well as scientific and professional concerns. The letter indicated that it was the potential commercial possibilities that might develop from the garden that caused the Department of Horticulture to support the request.

Apparently, Maxwell had made efforts to strengthen the request in yet another way by previously obtaining a promise of support from the U.S. Bureau of Plant Industry. The letter to the regents noted that the bureau had offered seeds, plants and cuttings to help start the garden.

As a result of those efforts, on April 6, 1914, the Board of Regents, upon the recommendation of President Bryan, adopted the following motion: "That there be authorized the establishment of a Materia Medica Garden for medicinal plants, particularly those of a commercial character. Such a garden to be operated in connection with the horticulture department, that department being credited and the pharmacy department being debited with the cost of labor."

That action of the board appears, on the surface, to have given Maxwell a positive direction for a project he greatly desired. Since the Department of Pharmacy did not have the equipment and other resources at the disposal of the Department of Horticulture, he had secured the cooperation of that department.

Perhaps Bryan had indicated, early on in discussions with Maxwell, that the proposal would be better received if it were advanced as a cooperative venture. He also might have felt that, for it to be successful, it would need the expertise available from the Department of Horticulture.

It is interesting to note, also, the emphasis placed on the development of the project as a source of information that might be used to promote commercial production of medicinal plants and that the educational value of the project apparently was considered to be of lesser importance.

Location and termination

The process used to determine the location of the authorized garden in 1914 may be looked upon now with amusement, and perhaps with some envy, 75 years later. Maxwell also wrote in his March 24, 1917, letter that President Bryan had granted use of a plot of land for the garden after "walking with me over various parts of the campus."

The site selected was "that tract extending from the southeast corner of the campus, said corner being formed by the line that marked the south limits of the campus and the line that marked the west side of the old Windus orchard."

That hillside location is marked now as lying between the building known as the Claudius Johnson Tower and the parking lot to the east and below the hill.

Changes in emphases in pharmacy programs as well as development of that area of campus for other uses led to the demise of the drug garden in 1948.

Our Story site map

Our Story main page | Our Story categories | Help Desk

Contact | Give | Advertise

Washington State Magazine | Washington State University | Class Notes

Our Story is coordinated by

In partnership with

Our Story and Washington State Magazine are publications of Washington State University. All rights reserved.

P.O. Box 641227, Washington State University, Pullman, WA 99164-1227 USA | wsm@wsu.edu, 509-335-2388

Accessibility | Copyright | Policies